10% Retirement Rule Explained: Does It Still Work in 2026?

10% Retirement Rule Explained: Does It Still Work in 2026?

The 10% retirement rule is one of the oldest and most shared ideas in personal finance. The rule is simple. Save at least 10% of your income every year for retirement. This money usually goes into accounts like a 401(k) or an IRA. Many people include employer matching as part of this 10%.

This rule became popular because it feels achievable. It does not scare beginners. It works well for people who start early and stay consistent. But the financial world of 2026 looks very different. Rising costs. Longer life spans. Higher medical expenses. These changes raise one clear question. Is saving 10% still enough?

Table of Contents

Key Takeaways

- The 10% retirement rule is a starting point, not a final plan

- Employer match is usually included in the 10% total

- Early starters benefit the most from this rule

- Inflation and longer retirements reduce its effectiveness

- Many experts now suggest 15% or more for safety

Also Read: 100 Minus Age Rule by John Bogle Explained Clearly: This Rule Built Millionaire Portfolios

What the 10% Retirement Rule Means

The 10% retirement rule means setting aside one tenth of your gross income every year for your future. If you earn 50000 per year, you aim to save 5000. This money is invested for long term growth.

Most financial advisors allow employer matching to count toward this number. For example, if your employer adds 5%, you only need to contribute another 5% to reach the target. This makes the rule feel more practical for working professionals.

The rule was built on old assumptions. Market returns around 7 to 10%. Moderate inflation. A retirement period of about 20 years. Under these conditions, steady saving and compounding could create a decent nest egg.

Why the Rule Became So Popular?

The biggest strength of the 10% rule is simplicity. People understand it quickly. It works well with payroll automation. Money is deducted before spending starts.

Public discussions on social platforms still praise this habit. Many users describe it as low effort and high impact. It builds discipline. It reduces anxiety about the future. It helps people start instead of waiting.

Auto enrollment trends also support this idea. Many retirement plans now default employees into savings rates near 10 to 15%. This shows how deeply the rule is embedded in retirement systems.

The Math Behind the Rule

The rule works best when time is on your side. A person who starts saving in their early twenties has decades for compounding. Even modest contributions can grow significantly over time.

But the math changes when income rises slowly. Young workers often earn less. Saving 10% of a low salary creates smaller balances. As income grows later, catching up becomes harder.

If someone saves 10% for 40 years with steady returns, the outcome may look reasonable. But very few people save the same amount every year for four decades. Career breaks. Job changes. Expenses. All disrupt the plan.

Why Many Say 10% Is Not Enough Today

Recent sentiment shows growing criticism. Inflation has reduced purchasing power. Healthcare costs continue to rise. People live longer after retirement. Taxes may increase.

In this environment, saving only 10% may lead to shortfalls. This is especially true for late starters. Someone who begins saving seriously in their thirties or forties needs to contribute more to reach the same goal.

High earners also face limits. Lifestyle expectations grow with income. A flat percentage does not always support future spending needs. Many experts now describe 10% as outdated for modern conditions.

Public Opinion from Recent Discussions ( Data Taken From X )

Online discussions from late 2025 and early 2026 show mixed reactions. Some still defend the rule as a foundation. Others call it unrealistic.

Supporters say it creates a habit. It removes decision fatigue. It helps people feel in control. Tweets often frame it as a starting step toward financial peace.

Critics argue that the rule ignores real life pressures. Housing costs. Student loans. Childcare. Medical bills. Many say a single number cannot fit everyone.

This shift shows a broader trend. People now prefer personalized planning over fixed rules.

How Employer Match Changes the Equation

Employer matching is often described as free retirement money. If your employer matches 4 to 6%, that is an instant return on your contribution.

Most advisors agree that the match should be included in the 10%. This makes the goal easier to reach. It also boosts long term growth without extra effort.

Missing out on a match is costly. Even small increases in contributions can add hundreds of thousands over time. This is why experts often say to maximize the match before anything else.

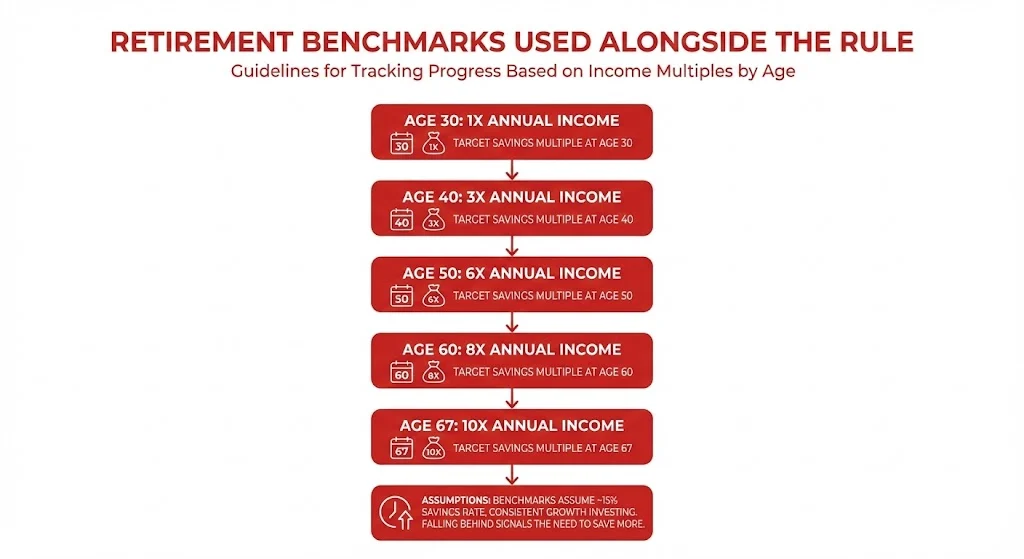

Retirement Benchmarks Used Alongside the Rule

Many guidelines are paired with the 10% rule to track progress. One popular framework suggests saving multiples of your income by certain ages.

Below is a commonly cited benchmark structure.

| Age | Target Savings Multiple |

|---|---|

| 30 | 1x annual income |

| 40 | 3x annual income |

| 50 | 6x annual income |

| 60 | 8x annual income |

| 67 | 10x annual income |

These benchmarks assume a higher savings rate closer to 15%. They also assume consistent investing in growth assets. Falling behind these numbers often signals the need to save more.

The Shift Toward 15% and Higher

In recent years, many firms promote a 15% total savings rate. This includes employee and employer contributions combined.

Data shows that people who save closer to 15% have more flexibility. They can handle market downturns better. They have room for healthcare costs and longer retirements.

Policy changes also reflect this shift. Auto enrollment features now increase contribution rates over time. Catch up contributions for older workers have expanded. These changes signal that higher savings are becoming the norm.

When the 10% Rule Can Still Work

The rule can still work under certain conditions. Starting early is the biggest factor. Investing consistently matters. Keeping expenses controlled helps.

People with modest lifestyles may need less income in retirement. Those with pensions or additional income streams may rely less on personal savings.

In these cases, 10% can be enough as a baseline. But it still requires regular review and adjustment.

When the Rule Fails?

The rule often fails for late starters. It fails for people in high cost areas. It fails when inflation stays high for long periods.

It also ignores debt and emergencies. Saving aggressively without a safety buffer can backfire. Many people withdraw retirement funds early due to financial stress.

This is why newer advice focuses on balance. Emergency funds first. Employer match next. Then gradual increases toward higher savings rates.

A More Practical Way to Use the Rule

Instead of treating 10% as a finish line, treat it as a floor. Start there if needed. Increase contributions with every raise.

Review your progress against income based benchmarks. Adjust for inflation and lifestyle changes. Use calculators to test different scenarios.

The goal is not perfection. The goal is sustainability. A flexible plan beats a rigid rule.

Bottom Line

The 10% retirement rule still has value. It helps people start. It builds discipline. It works best as an entry point.

But in 2026, it should not be treated as a complete plan. Longer lives. Rising costs. Economic uncertainty demand higher awareness.

Saving 10% may be enough for some. For many, it is only the beginning. The smartest approach is to use the rule as a guide and then build a plan that fits your real life.

Tags: retirement planning, personal finance rules, retirement savings, 401k strategy, long term investing, financial planning basics

Share This Post